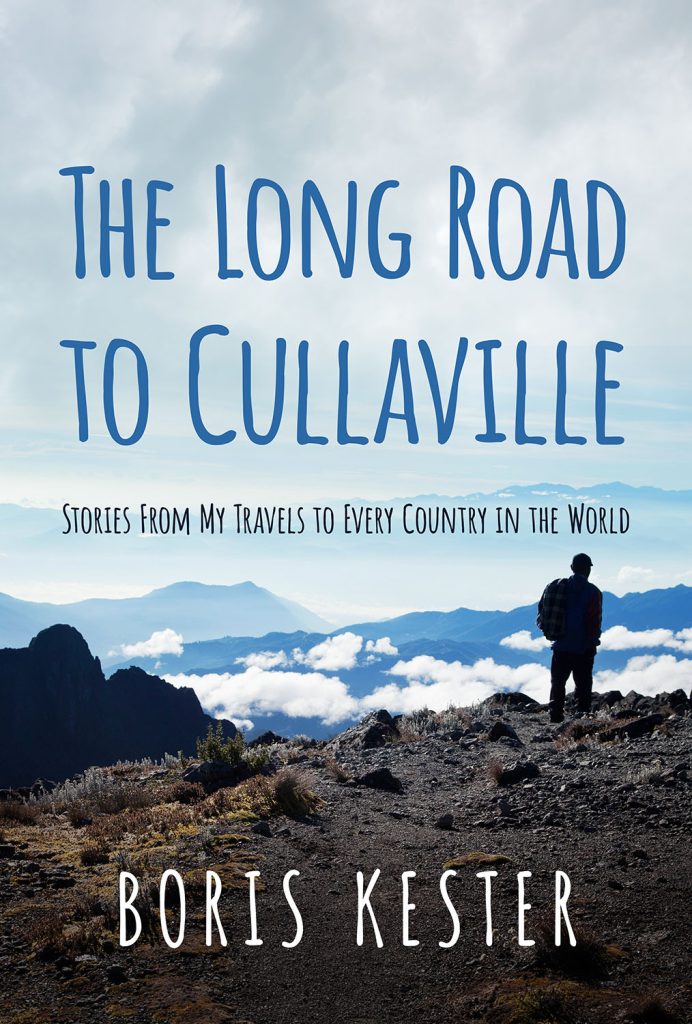

Introduction

“A ship in harbour is safe, but that is not what ships are built for.”

—John A. Shedd, Salt from my Attic, 1928

“You can never cross the ocean until you have the courage to lose sight of the shore.”

—Christopher Columbus

“Isn’t it dangerous to travel to all those weird countries?” That is the question I’m most frequently asked (after “what is the most beautiful country in the world?”). Perhaps an obvious one to ask someone who has visited them all. To me, it’s all a matter of perception. My motivation to travel is fired by an unbridled curiosity for unknown places, for people with very different lives and for cultures that are remote from mine. I’m elated when I cross a border to a new country and can crave for all the new things I’m going to see and do. I can be intensely happy when I meet extraordinary people and when I encounter natural or man-made beauty that overwhelms me. When strangers invite me wholeheartedly into their lives. My heart starts to beat faster when I embark on something without having a clue how it will end. Where others might see danger, I see adventure.

After I decided to travel to all the countries of the world, I compiled a list of the 75 remaining. I used the only objective definition of “country”: the one used by the United Nations. At the time, it consisted of 192 countries; South Sudan was added a few years later. As soon as you divert from this list, you quickly get bogged down in a subjective, complicated, endless and often politically charged discussion – which can be entertaining and exhausting at the same time. Among the remaining countries were destinations that many would consider “dangerous”. Somalia, Iraq, the Central African Republic and several others that, according to all current travel advice, had been coloured deep red for years, and where you were advised not to go. “Don’t travel to Somalia. Are you there now? Leave the country as soon as possible […] Serious crime occurs in this country; including armed robberies, robberies, kidnappings, murders, explosions, and sectarian violence.”: I have read more compelling promotional holiday brochures. Nauru, Tuvalu and São Tomé & Príncipe: although not on the red list, I had never heard of them either. Where were those countries really, and how could I get there?

I quickly realised that I had set myself a goal of which I could not foresee the consequences. I wasn’t even sure whether it was feasible in the first place. Excitement took possession of me. It was clear that I found myself at the beginning of the greatest adventure of my life. The more I thought about it, the more enthusiastic I got. It would certainly be exciting. But dangerous?

During one of my many Interrail wanderings, in my early twenties, I overheard a few young Americans exchange experiences about their travels across Europe. The sights not to be missed, the best food, the most beautiful cities. Barcelona, Venice and Athens were all high on their list. Then they talked about where you should avoid going. One of them mentioned Amsterdam. He had heard several stories of people who had been robbed. A girl supported him: she too had been told that it was unsafe. The others nodded in agreement. In no time, they labelled Amsterdam as the most dangerous city in Europe and decided to steer well clear of it.

I could hardly believe what I was hearing. They were talking about my city! I lived there, cycled through it day and night without ever feeling threatened or unsafe. Yes, a junkie once stole my bike. But to call that dangerous? It made me realize for the first time how biased and unreliable the advice and warnings of others can be, how easy it is for people to frighten each other and how a bad reputation, once obtained, is very difficult to erase.

How often was I warned during my ramblings about the people in the next village, the next region, the capital or (especially!) the neighbouring country. They’re all crooks, they’re unreliable, it’s dangerous: don’t go there! Only to discover on the spot that the inhabitants received me like a prodigal son with the corresponding treatment. But when I left they would warn against the residents of the next village. They really couldn’t be trusted!

What is that about? Is there an ingrained sense of superiority in people? An aversion to everything different and odd? Fear of the unknown? The unknown is precisely what the traveller longs for, which drives him to go on and on to the next place he wants to discover. Granted, the unknown by definition also entails risk. But risk is not necessarily the same as danger.

By nature, humans are equipped to assess risks and make decisions when facing dire situations. Those decisions are by no means always rational. Our brains have set up a beautiful system in which fear, an expected reward, and emotions work together to assess and act on risks. Confronted with acute danger, we have the well-known freeze, fight or flight reaction. That has helped humanity to survive for many centuries in all kinds of frightful situations.

In recent decades, we have done everything we can to eliminate as many risks as possible and make life as safe as possible. We have created labels, warnings, regulations and much more to achieve this which, in many cases, has certainly been useful. For example, cars, aeroplanes and trains have now become so safe that we use them without even thinking about possible dangers, convinced that we will arrive safely.

Gradually, we have come to think that we can fully control life and that we can exclude all risks. We have forgotten that certain risks are inherent in life and that destiny still has the final say. Besides, taking risks doesn’t always have to be negative. Look at it from the other side: if we never dared to do anything, everyone would stay in their comfort zone. Many inventions and discoveries would never have been made. Columbus would never have crossed that ocean. We would never improve in our lives: we would not dare to ask that girl or boy that we have set our eyes on for a date.

Travel and adventure go hand in hand. They don’t exist without taking risks. Images and reports about terrorist attacks and insecurity flash around the world in a matter of milliseconds. They enlarge the risks, feed the fear and put the “Dangerous” stamp on a country. Once obtained, it’s very hard to get rid of. It’s because of those images that people ask me if all that travelling isn’t dangerous and whether I have gone mad.

Reality on the ground is always different. Often very different. Especially because of the people I met on the way, I realised that the large majority of people around the world are kind to their visitors. This also applies to countries that are supposedly dangerous – or even more so there. Man is apparently keen to welcome the stranger and to protect him. That helped me a lot to have confidence and bring my travels to a happy conclusion. Was I scared? No. Fear is a bad counsellor, especially for the traveller. This is certainly so for the traveller who wants to go to all countries in the world.

In this book, I will take you along on travels where risk was unavoidable. In every chapter, situations arise where I have to make choices, often without overseeing the consequences. Some chapters are situated in countries that are generally labelled “dangerous”. Others describe adventures with people I met along the way, obstacles I had to deal with to achieve my goal, as well as moments where I was plain lucky – or not. The bottom line is that I rarely opted for the easy way. I leave it to the reader to judge the sanity of my decisions.

Allow me to take you along to Somalia and Yemen, Cameroon and Kyrgyzstan, Nauru and Afghanistan, and other destinations that are probably very different from what you would expect beforehand. Just like those countries surprised me when I travelled there. And I always came back safely.